Stocksbridge

Congregational (Congs)

now Christ Church

In grateful memory of the members of this Congregation who gave their lives for their country in the Great War 1914-1919.

And those who gave their lives in the Second World War 1939-1945

Photo credit: Sally Jowitt

THE GREAT WAR

Alfred Beckett

Bertie T. Catton

Donald Crossley

Frank Eastwood

Charles England

Jesse H. Kenworthy

Frank Lievesley

Thomas Milnes

Eric W. Sheldon

Ernest Watson

THE SECOND WORLD WAR

Edward Challis

Aubrey Rodgers

Albert Sellars

The Congregational Church stands on Manchester Road at the bottom of Hole House Lane. It had been known by several names over the years; it was originally known as the Salem Chapel, then the Congregational (or the “Congs”) and is now known as Christ Church and is a joint United Reformed and Methodist Church.

It was built by Mr. Ridal in 1863 and opened on 9 October 1864. The only other church nearby was the Ebeneezer Chapel, which later became the British Hall. The two were amalgamated in 1881. Further away was Bolsterstone Church and Midhope Chapel.

Ten men from the congregation died serving during World War 1. After the end of the war the church, in common with other places of worship, gave a thanksgiving service, which was very well attended. In 1919 the members of the church hosted a “welcome home” tea and concert in the British School which was attended by demobilised and discharged soldiers.

At some point a memorial was sited in the church to those men who had lost their lives in the conflict, but this was destroyed when the building was completely gutted by fire in November 1921 [see here for more information]. As far as I know, there are no photographs of it, but it was made of marble.

The church was rebuilt in almost the same style as before and re-opened in 1923. On Sunday 22 June 1924 Councillor Joseph Sheldon, C.C., whose grandson Eric William Sheldon is named on the memorial, unveiled a new brass War Memorial tablet which had been presented to the church by an anonymous donor. A procession set off from Smithy Hill, headed by the Stocksbridge Prize Band, and followed by the members of the British Legion, led by Major H. McIntyre. The church was packed. Major McIntyre spoke, and Joseph Sheldon described how the graves of those who had died abroad were tended. He said that relatives and friends of the fallen who visited the graves were given every help to locate their loved ones’ graves. He then unveiled the Memorial and Major McIntyre read out the names. Colonel Charles Hodgkinson also spoke, saying that as far as the present generation was concerned there was no need of a memorial of brass because the memory of those men was enshrined in their hearts. But that generation would pass away and it was the object of the tablet that those names should be handed down in honoured remembrance.

There is a second brass tablet which has been added to the first, which contains the names of three men of the congregation who lost their lives in World War 2.

As well as its own War Memorial tablets, Christ Church also holds tablets which have been removed from The Primitive Methodist Chapel / West End (now The Rugby Club) and the Deepcar Wesleyan Chapel (now converted into accommodation).

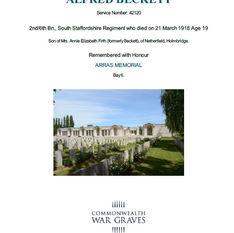

Private Alfred Beckett 42120

Served with: 2/6 Bn. South Staffordshire Regiment

Killed in Action: 21 March 1918 aged 19

Commemorated on local memorials at: Clock Tower, Stocksbridge Congregational; also on the Holme and Holmbridge Panel of the Holme Valley War Memorial which is in the grounds of the Holme Valley Memorial Hospital

Commemorated in France on the Arras Memorial, Bay 6 (no known grave)

Alfred Beckett was born in Stocksbridge in 1898 but left the district when he was a child. However, as a local lad, he was still entitled to be commemorated on our local War Memorials. His parents were Alfred Beckett and Martha Ellen Pears, who married in 1892. Alfred senior had been born in Holmfirth and his family came to live in Stocksbridge when he was a young boy. He was a bricklayer by trade. Martha Ellen died in 1899 and Alfred married again to Annie Elizabeth Wragg. He died in 1907 and his widow married Benjamin Firth the following year. They had moved to Holmfirth by 1911, and young Alfred worked at Clarence Mills, Holmbridge, before joining up when he turned 18. His service record does not appear to have survived.

Alfred turned 18 towards the end of 1916 and enlisted in Huddersfield early in 1917. After training he was sent to France towards the end of the year. He was reported missing on 21 March 1918. In July 1918 the Red Cross received a notification, in German, dated 22 June, regarding Alfred, among others. The document consisted of a list of ID tags which had been taken from those killed in action on a battlefield between Quéant and Noreuil in March 1918. Quéant is about 14 miles from the centre of Arras, and 2 miles from Noreuil. The Huddersfield Daily Examiner reported in its 28 November edition, printed a couple of weeks after the Armistice, that Alfred had now been officially presumed killed on the date he was reported missing.

Sergeant Bertie Thorpe Catton 42444, previously 17492

Served with: 6th (Service) Battalion, Leicester Regiment

Formerly 17492 York & Lancaster Regiment

Died: KIA 18 September 1918, France & Flanders

Commemorated on local memorials at:

Commemorated Vis-en-Artois Memorial, panel 5, France (no known grave)

Bertie was born in Bradford in 1892 and was living in Langsett when he enlisted in Sheffield. He was the son of William Thorpe Catton and Emily. William had been born in Knaresborough and Emily in Bradford. When the 1891 census was taken they were living in Bradford and William was working as a coachman and domestic servant. Going by the dates of birth of their children, the family moved here between 1895 and 1898. They lived at Bessemer Terrace and William worked as a house painter. I have been able to find out very little about Bertie’s time in the army. His Service Record does not survive and I could not find anything in the newspapers about him. He was killed in action in France in 1918 and has no known grave. After the war the family moved to Thurlstone.

Private Donald Crossley 52392

Served with: 2nd Bn., King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

Killed in Action: Avesnes, 7 November 1918 aged 20

Commemorated on local memorials at: Clock Tower, Congregational Church

Buried: Avesnes-Sur-Helpe-Communal Cemetery, Nord, France.

Donald Crossley was born at Horner House on 21 July 1898 the son of George Herbert Crossley and Edna Dyson. When the 1911 census was taken the family were living at High Geen. Donald was 12 years old. They moved back to Stocksbridge and Donald worked at Stocksbridge colliery. In 1918 the family were living at 602 Manchester Road in one of two houses (600 and 602) built by George Herbert’s father Ralph Crossley. Donald’s Service Record has not survived, but we know that he enlisted in Sheffield and that he was killed in action at Avesnes on 7 November 1918, just four days before the end of the war was declared. His parents chose a personal inscription for his headstone, “Christ is the Path and Christ the Prize.” He is also remembered on his parents’ headstone in Bolsterstone churchyard. Donald’s younger brother Dyson Crossley was killed in an accident in the steelworks in 1939 when he was knocked into the ingot cooling pit by a bolt falling from an overhead crane. He died later from the burns he received. He was 25 years old. Donald’s sister Ruth Crossley was well known in this area as a midwife until she retired in 1971.

Private Frank Eastwood 2387

Served with: B Company, 1/4th (Hallamshire) (TF) Bn. York & Lancaster

Killed in Action: 13 July 1915 aged 19

Commemorated on local memorials at: St. Matthias, Clock Tower, Congregational Church

Buried at: Talana Farm Cemetery, Belgium

Frank Eastwood was born in 1896 to George Eastwood and Frances Tunnicliff. The family were living at Goit Terrace (267 Hunshelf Road) when the 1911 census was taken and Frank was 15 years old, working as an assistant draper for the Co-operative Society. Frank enlisted in Sheffield into the York & Lancaster Regiment. His war record survives and tells us that he was 5’ 9¼” tall, weighed 9 stones 10lbs and that his physical development and sight were good. On 13 April 1915 he embarked for France at Folkstone and was killed just three months later, on 13 July. His parents chose an additional inscription for his headstone; “At the going down of the sun and in the morning we will remember him.”

Later that month the Congregational Church held a service in intercession for him (intercession is the act of praying on behalf of others, often seeking God’s mercy, guidance, or intervention). The vicar read out the names of all the young men connected with the church who had gone to the Front, and mentioned them in prayers. He specially mentioned two young men who had been connected with the church and Sunday school and who had died; Frank Eastwood and Frank Lievesley. The committal part of the burial service was read with the members of the congregation standing.

Private Charles England 99368

Served with: 2/6 Bn. Durham Light Infantry

Formerly Tr/5/69851 Training Reserve

Killed in Action: 25 September 1918 aged 20

Commemorated on local memorials at: Clock Tower & Congregational Church

Buried: Vieille-Chapelle New Military Cemetery, Lacouture, Pas de Calais, France

Charles was the son of Charles England and his wife Lucy Moxon, and he was born in 1898. His father worked for the Co-operative Society and in 1911 they were living in the Co-operative Houses on Manchester Road, Deepcar. Young Charles was 12 years old and still at school. Previous to this they had lived at Low Lane [Victoria Road], Bracken Moor. He went on to work in the general office at Fox’s.

His service record survives, although much of it is illegible. It tells us that he was 5’ 2” tall, weighed 6½ stones, was working as a clerk, and that his religion was Congregationalist. He had a scar between the index and second finger of his right hand. Slight “defects” were noted, which were not sufficient to cause him to be rejected for service; he had false teeth and overlapping toes. Charles’s Service Record is difficult to read in places, but it seems he was not initially thought suitable for front-line duty.

Charles attested on 8 July 1916 in Sheffield into the Durham Light Infantry, being allocated to the army reserve the following day. He was mobilized in May 1917 and transferred to a training reserve battalion in July. There was another transfer in September to [illegible entry] followed by a transfer into the 18th Battalion of the Yorkshire Regiment, which was initially for men who would serve only at “Home.” However, he was then transferred to the 2/6 Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry on 23 April 1918. He died in France on 25 September that year.

There is a photograph of Charles in the book Around Stocksbridge Vol 2 p.66 published by the Stocksbridge Local History Society and the accompanying text says that he was killed by a single piece of shrapnel that hit him in the head while he was in the canteen behind the lines.

His parents chose some additional words to add to his headstone: “They were a wall unto us, both by day and night, and we were not hurt.” The Commonwealth War Graves Commission records that his parents were living at Mercer Lea, Deepcar.

Charles now lies in the Vieille Chapelle New Military Cemetery, but this was not his first resting place. In June 1920 his father received a letter informing him that, “owing to the agreement with the French and Belgium Governments to remove all scattered graves for concentration in proper cemeteries it has been found necessary to exhume the body of [Charles England] for re-burial in Vieille Chapelle New Military Cemetery, 5 miles North North East of Bethune. I am to say that the necessity for the removal is much regretted, but was found unavoidable for the reasons above given. I am to assure you that the work of re-burial has been carried out with every measure of care and reverence, and that special arrangements were made for the appropriate religious service to be held.”

Corporal Jesse Haworth Kenworthy 18/98

Served with: A Company, 18th Bn. Durham Light Infantry

Died of wounds: 17 August 1916 aged 25

Commemorated on local memorials at: Bolsterstone, Clock Tower, Congregational Church

Buried at: Chocques Military Cemetery, France

Jesse Haworth was the son of our esteemed local historian, Joseph Kenworthy of Stretton Villa, Deepcar, and his wife Anne Bocking. He was born in 1891 and was a member of the Congregational Church. He attended the British School before going on to Penistone Grammar School. He taught and took part in the work of the Sunday School. As a young man he was apprenticed in the steelworks, entering the engineers’ department at Fox’s as a draughtsman in 1905 whilst continuing to study at evening classes held in connection with the University of Sheffield. In 1913 he left Fox’s for an appointment at Messrs. Bessemer’s works in Sheffield, before moving up north to Darlington Forge. He was there when war broke out in August, 1914 and he attested into the Durham Light Infantry in September, a month after war was declared. His Service Record has survived, and it tells us that he was 5’ 8½” tall, with a fresh complexion, hazel eyes, light brown hair. He narrowly escaped death during the bombing of Hartlepool in December 1914. After over a year spent in training, he left these shores on 6 December 1915 bound for Egypt, disembarking on 22 December.

He spent two months in Port Said before sailing for France, arriving on 11 March 1916. On 20 June 1916 he was appointed to the rank of Lance Corporal, and was promoted to Corporal a month later. He saw a good deal of fighting but his death came as a result of his own carelessness. Since joining the fight at the Western Front, his duties involved “bomb throwing,” that is, hand grenades, or Mills Bombs as they were known. On 17 August 1916 he was tasked with inspecting bombs; he had to examine the whole bomb including the removal of the pin. A witness said that he saw Jesse cleaning the bombs, and the pin on one of them was rusty. He pulled out the pin and the lever sprang up, prompting the witness to run away. Jesse transferred the bomb into his right hand (presumably to be able to throw it away with more accuracy) and went to throw it over a parapet but it exploded almost as soon as it left his hand, about 5 seconds after the pin had been withdrawn. Jesse was admitted into a field hospital as a result of the injury this caused to his right shoulder (recorded as GSW or gunshot wound, although it wasn’t a bullet that caused the injury). He died the same day. An inquiry was held, and it found that Jesse was at fault for not taking the detonator out before withdrawing the pin. Someone examined the remaining eleven bombs and, although they were rusty, there was nothing wrong with them that would have caused a premature burst.

Jesse’s parents were informed by telegram of his being wounded, although understandably, nothing was mentioned about the cause of the accident, they being led to believe he had been shot; Killed in Action. His father wrote a reply: “Dear Sir, re. my beloved son, am greatly distressed to receive your telegram. Kindly inform me as to how I can get into communication with No. 1 Casualty Clearing Station as to his condition and how soon and where I could see him. Do please help me all you can and as promptly as you can. Kindly telegraph me tomorrow. Yours truly, his father, Joseph Kenworthy.” A few days later they received another telegram informing them of his death. Joseph wrote once more, on 3 November, asking about his son’s personal effects: “Dear Sir, I do not wish to unduly add to the great pressure of work that falls upon your department in these trying times, neither would I leave undone what affection urges me to do, viz:- Will you kindly say if you have received any articles of private property left by my late son Corporal Jesse H. Kenworthy of the 18th Battalion Durham Light Infantry no. 98 who was killed August 17 1916. Do please let me know, also inform me re. the procedure necessary to obtain them.

His parents received a letter from Captain J. B. Hughes-Gamas, dated 20 August 1916: “It is with feelings of the very deepest regret that I have to inform you of the death of your son, Cpl. Jesse H. Kenworthy, who died as a result of his wounds received in action. I cannot sufficiently express the sympathy I feel for you and all his relations and friends in your sad loss. His loss is a very severe one to the battalion, too, as his work was regarded as extremely valuable. He was an excellent N.C.O., and his name had just been sent forward for promotion to sergeant. He was held in the highest esteem by officers, N.C.Os, and men, and deservedly so, for he always displayed the utmost coolness and resolution in times of danger, and could always be relied upon to the highest degree. Once more let me say how very sorry I am to have to convey to you such sad news.”

Another officer wrote: “I knew him very well, and know he was one of the best fellows that ever lived. His friends all say how earnest he was, devoted to his duty and very brave, because he had before him always the strength that God gives to His children.”

One of his comrades, writing on behalf of the Battalion Bombing Section, of which he was in charge, said: “He was a very fine fellow indeed. His coolness knew no bounds, his presence amongst us and his encouraging words and smile during our most trying times in the line, proving of a great assistance to us all.”

Jesse was buried in the Chocques Military Cemetery, France. He was 25. His parents chose a personal inscription for the headstone: “Faithful unto Death” A few lines were printed in the Sheffield Independent: “As ‘Soldier of the King’ he served / Nor from the path of duty swerved / As ‘Soldier of the King’ he died / With Him for ever to abide.”

An article printed in the local paper after his death became known paid tribute to him. “His love of work, coupled with a high sense of duty, endeared him to a wide circle of friends in temporal and spiritual matters, to which ample testimony is borne in the many touching tributes conveyed by officers and men, chaplains and comrades [and] to his sorrowing parents.” The managing director of the Darlington Forge wrote: “I much regret to learn of the death of Cpl. Jesse H Kenworthy, your son. He was greatly esteemed by his colleagues in our drawing office and by the whole staff, and he had before him a promising career. He will always be remembered as one of our staff and of the many others who have sacrificed their lives at the call of duty for king and country.” Joseph’s brothers Frank Belcher and Joseph Aubrey both served in France and survived the War.

Private Frank Lievesley 17689

Served with: 3rd (Reserve) Bn York & Lancaster Regiment

Died: 4 March 1915

Commemorated on local memorials at: Clock Tower, Congregational

Buried at Stocksbridge Congregational Church

Frank was born in 1893 and was the son of Thomas Lievesley and Sarah Ellen Poole who lived at Hawthorn Brook. His mother died in 1909 aged 43. When the 1911 census was taken Frank was 18 years old, single, and working as an umbrella tool maker in Fox’s. Frank enlisted at the age of 21 into the 3rd (Reserve) Bn. York & Lancaster Regiment on 14 December 1914 after attending a recruitment meeting at Deepcar. He was sent to South Shields in January 1915, but it seems he struggled with the army life. It had been reported that he had been unable to do the physical exercises, and that he was thought to be “a little strange” in his mind. He was sent to see a doctor, who put him on the sick list for ten days. Frank committed suicide by throwing himself out of a window on 4 March 1915, having served for just under three months. A coroner’s inquiry concluded that he committed suicide by throwing himself out of a third-storey window whilst temporarily insane.

His body was brought back to Stocksbridge for burial. His comrades accompanied his coffin, which was draped in the Union Flag, to the railway station at South Shield. There was a firing party of 25 men, and altogether around 150 men from the York & Lancaster Regiment paid their last tribute to him at the station. The funeral took place at the Congregational Church, with many people, including soldiers, lining the road outside. The coffin had been provided by his comrades in the Regiment and the cost of the funeral was met partly by his family and partly by the army. He was buried to the east of the church, near the entrance. Special prayers for the men of the congregation who had gone to the Front were said during an intercession service in July 1915, with special mention of Frank Lievesley and also Frank Eastwood, who had died in France.

Private Thomas Milnes 10103

Served with: 2nd Bn. Auckland Regiment NZ Expeditionary Force

Killed in Action: 14 September 1916

Commemorated on local memorials at: Clock Tower, Congregational Church

Commemorated at: Caterpillar Valley (NZ) Memorial, which is in the Somme region of France (no known grave)

Thomas was born on 10 July 1885 and was the son of Thomas Milnes and Frances Hannah Hayward. His mother died in 1888 while he was still a young child, and his father married again to Martha Brooke. They were living at Watson House Farm when the 1901 census was taken. Thomas senior was a farmer, and Thomas junior worked on the farm. His step mother died in 1907 and his father went to farm at Inkerman Farm in Denby Dale. In 1911 Thomas was living with his father but his occupation was now butcher.

Thomas emigrated to New Zealand in around 1912. He first took up farming near Waikato before moving to Christchurch before relocating again, to Auckland. He enlisted with the 2nd Battalion of the Auckland Regiment in December 1915, a few months after the outbreak of war. On 1 April 1916 Thomas sailed with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force out of Wellington, bound for Suez, Egypt. He either sailed on HMNZT 49, the Steamship Maunganui, or HMNZT 50, the SS Tahiti. A short while later he came back to England, spending a brief period training on Salisbury Plain before going out to France. An enormous infrastructure of camps, hospitals, depots and offices was developed in England to support the New Zealand Expeditionary Force on the European continent. At first, Sling Camp on Salisbury Plain was the only training camp for New Zealand servicemen in England, although others were later established. New Zealand’s sick and wounded soldiers were ferried from France to England on hospital ships.

Thomas was sent across the Channel to France in July 1916 and was killed in action on 14 September 1916. He would have been about 31 years old. He is commemorated at the Caterpillar Valley (NZ) Memorial, which is in the Somme region of France. A record held by the New Zealand archives confirms that Thomas’s father was Thomas Milnes of Inkerman Farm, Denby Dale.

A New Zealand soldier wrote of Thomas in a letter, “His bright and humorous disposition made him very popular. Always optimistic, always seeing the funny side, and always jocular, he was a great favourite in tent or hut or on parade.”

Lance Corporal Eric William Sheldon 2342

Served with: 1st/4th (Hallamshire) (TF) Battalion York & Lancaster Regiment

Killed in Action: 27 August 1915

Commemorated on local memorials at: Clock Tower, Congregational Church; also St. Andrew’s Church, Sharrow

Buried: Talana Farm Cemetery, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium

Eric William Sheldon was born at Stocksbridge on 8 November 1893 to Frank Sheldon and Elizabeth Milnes. They lived at Beech Mount, Bracken Moor but had also lived in Sharrow, Sheffield. Before being called up, Eric had worked in Fox’s. Eric enlisted in Sheffield on 7 September 1914, a month after the outbreak of war. His address then was Grange Crescent, Sharrow. He married Ruth Withers in 1915, probably in Sharrow. On 13 April 1915 he sailed for France, and was promoted to Lance Corporal on 11 August. He was killed in action later that month, on 29 August 1915. His service had not lasted a year. After her husband had been posted abroad, Ruth went to live with her father at Stable House (formerly known as Coach House), 291 Ford Lane. Shortly afterwards she gave birth to a daughter, Mabel, but she only lived a few days and he never got to see her.

The first Remembrance Service at the newly-built Clock Tower War Memorial was held in 1924. The first person chosen by the British Legion to lay a wreath was Ruth’s father Henry Withers. Four of his sons had served in the War, but only one came home, and it was because Mr. Withers had the most names on the Roll of Honour that he was chosen to place the first wreath. So not only did Ruth lose her husband, she also lost three brothers; Henry Oscar, James Herbert, and Joseph Adin Withers. It was Eric’s grandfather, Joseph Sheldon, a local councillor, who was on the committee responsible for the construction of the Clock Tower War Memorial and was present at both the laying of the foundation stone and the Memorial’s dedication on Saturday 1 December 1923.

Below is a photograph of Eric with his pals Oscar Norris, Frank Thickett, D.C.M. and Tom Scarrot. In 1916, a year after his death, they placed an In Memoriam notice in the Sheffield Evening Telegraph: “In loving memory of Lance-Corporal Eric William Sheldon, who was killed in action August 27th 1915. From his comrades Oscar, Frank and Tom”

Private Ernest Watson 688

Served with: 13th Battalion, Australian Infantry

Killed in Action: 4 February 1917 aged 32 [he was 31, almost 32]

Commemorated on local memorials at: Clock Tower, Congregational Church

Buried / Commemorated at: Villers-Bretonneux Memorial, France, the Australian national war memorial erected to commemorate the Australian soldiers who fought in France and Belgium during WW1

Ernest was born at Horner House (probably at River View at the bottom of Pearson Street) on 24 January 1886 to William Parker Watson and Caroline Dawson. Both his parents had been born in Lincolnshire, and married in that county in 1871. They settled at Hawthorn Brook, Stocksbridge, and William worked in the colliery. When the 1901 census was taken, Ernest was 15 years old and working as a trammer in the coal mine. Caroline died in 1902. When the 1911 census was taken, Ernest was 25 years old, single, and still working in the pit.

Ernest went out to Australia sometime between 1911 and 18 September 1914 when he joined up with the 13th Battalion of the Australian Imperial Force at Sydney, New South Wales. His service record is available, but is at times contradictory, with his age, father’s name and religion all differing in the same document. From this record we learn that Ernest was 5 feet 6½ inches tall, weighed 11 stone 6 pounds, had a dark complexion, black hair and brown eyes, and had tattoos on both his arms and chest.

On 22 December 1914 Ernest embarked at Melbourne aboard H.M.A.T Ulysses (A38), arriving in Alexandria, Egypt, on 31 January 1915. In April he headed for the Dardanelles to join up with the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. He was wounded at Gallipoli (Turkey) about a month after arriving, receiving a gunshot wound to his buttock, and was admitted to no. 2 Australian General Hospital, which at that time was in the Gezira Palace in Cairo, Egypt. Ernest then spent some time recovering, firstly in Helouan, in what was the Al Hayat Hotel, which was being used by the Australians as a convalescent camp, and then in a British Army hospital at Ras-el-tin, overlooking the harbour of Alexandria. He didn’t return to the Front until early August 1915 when he sailed from Alexandria to rejoin his unit on the Gallipoli peninsular.

Ernest was admitted to hospital again in November 1915, suffering from a septic hand. He was treated on a Hospital Ship and taken from Mudros on the nearby Greek island of Lemnos back to Egypt, to Chesireh, Cairo, in December. He did not re-join his Unit until 6 February 1916. Less than two weeks later he was confined to barracks for two days for leaving the ranks whilst on parade. In June of that year Ernest sailed from Alexandria to join the British Expeditionary Force in France, landing at Marseilles on 8 June. At the end of that month Ernest was disciplined for neglecting to obey an order, and for being absent from the roll call on 21 May and on 25 June. He received 10 days “field punishment no. 2.” Field Punishment no. 1 involved being shackled to an object such as a post, gun or wheel for several hours a day. Field punishment no. 2 differed in that the offender was not attached to a fixed object and could still march with the men. Both types of punishment could also involve loss of pay and hard labour. Ernest was in trouble again in November, this time for drunkenness. His punishment was the same – Field Punishment no. 2 – but this time it was for 28 days. Ernest was back in hospital in December with quinsy, a rare and potentially serious complication of tonsillitis. He rejoined his unit on 13 January 1917 but was reported as missing in action on 4 February. His death was later confirmed, and he was buried near Gouedecourt by the Rev. Rentoul, the Chaplain with the 59th Battalion of the Australian Imperial Force. This should probably say Gueudecourt, which is in the region of the Somme. This is around 25 miles away from the Villers-Bretonneux Memorial, so perhaps, as sometimes happened, Ernest's body was removed after the initial burial. In his Will he left all his property and effects to his older sister Ada Rowbottom.

Penistone, Stocksbridge and Hoyland Express, etc. 03 July 1915, p7

A STOCKSBRIDGE BOY’S EXPERIENCES. With the Australians in the Dardanelles .

Being in Australia when war was declared, Pte. E. Watson, of Hawthorn Brook, Stocksbridge, joined the Australian Forces. He is now in Hospital in Cairo recovering from wounds. The following are extracts from letters received by his friends:

“We were told before we started that we were to attempt something hitherto unequalled in modern warfare, and that we were to accept heavy losses. We started to land on the coast of Gallipoli on a Sunday morning, just as dawn was breaking. At the place where we landed were two big hills, bigger than those around Stocksbridge, and very steep. Our method of landing was by small boats from the transports; the first two boats were smashed to pieces by shells, and all the poor chaps done for. Then the Navy got to work - you should have heard the noise! - it was indescribable. As soon as we were on the beach we downed our packs, fixed bayonets, and up the hills we went. Our orders were to clear the enemy from these positions, and entrench on the second hill. These Australians were completely mad, and we rushed three miles further inland than we should have done. Here we had our heaviest losses; the Turks let fly with their machine guns, and having no artillery of our own we were obliged to retire. The worst part of it was that we had to leave our wounded, and afterwards we found they were mutilated horribly. These Turks are wretches; they fire on the Red Cross and poison water. They can fight in defending a position, but in attacking are rotten. They fear neither rifle nor machine gun, but cold steel they will not face. Just word about the R.A.M.C. fellows: they’re fine. They need all the pluck and nerve they possess. I’ve seen them in hospital and on the field; and take off my hat to them. These Colonials are big fellows; we English look rather little beside them. They are daredevils; I needn’t tell you about their bravery; you’ll have read of it. I’ve seen it. How is the war affecting you at Stocksbridge? Fellows out here say that trade is very good in England. Whatever you have to suffer, may you never know the real horrors of war.”

SOURCES:

Military records at Findmypast and Ancestry

Army pension records at Ancestry / Fold3

Baptisms, marriages, burials, census returns at Findmypast and Ancestry

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Soldiers died in the Great War database

General Register Office for births and deaths

British Red Cross records at Findmypast

Newspapers at Findmypast (also available at the British Newspaper Archive)

Findagrave for headstone photographs

Australian records at www.naa.gov.au/ including Ernest Watson's 24 page Service Record

The Australian War Memorial site is very good www.awm.gov.au/

My own family history research and that of my late “pen pal” Mary Scoberg of Australia

All other one-off sources named in the write up

All research is my own, but I have checked it against that done by Michael Parker in his book Poppy People, to which I contributed some information at the time. If you want to know more about the army life of the men on our war memorials, there is a copy of his book in Stocksbridge Library. Since he wrote it, many more records have become available.

© Claire Pearson 2024