WILLIAM BATEMAN REDWOOD

1877-1920

Research into a Sheffield man who fought in France for nine months, served back in England until 1919, and who died at Wharncliffe War Hospital in 1920.

This research came about because I was intrigued by a story told to me by Dave Emsley of Deepcar about his great grandfather, William Bateman Redwood. The family story was that William died “3 days too late” for his widow to claim a War Widow’s pension, and that in the end she got nothing. William died in 1920 at the Wharncliffe War Hospital of the injuries he received in the war. The family also say that he had been the victim of a gas attack whilst fighting in France, but this is not recorded on the official records.

Service

William had been born in Gloucestershire in 1877 to William and Fanny Redwood. The family moved to Sheffield, and when William enlisted on the 10th September 1914 he was living at 23 Ulverston Road, Sheffield. He served originally as a Private in the 4th (Hallamshire) Battalion York & Lancaster Regiment (regimental number 2402), later transferring to the Durham Light Infantry (no. 351761). His service record states that he had previously served 1 year in the Bristol Rifles. He was in England until the 2nd April 1915 and seems to have been given leave before arriving in France on the 13th April. He was there for nine months, and was wounded in August 1915. A page in his Service Record states “Wounded B.E.F. [whilst with the British Expeditionary Force] Gun S. W. […].” (some of the writing is illegible). This was not necessarily a gunshot wound, because this phrase was also used to refer to shrapnel injuries. He was reported as a casualty in the Sheffield newspapers.

After arriving back on these shores on the 15th January 1916 he served a further 3 ½ years in England before being discharged under Paragraph 392 (XVI) of the King’s Regulations on the 19th June 1919 at the age of 42. This clause meant that he had been released on account of being permanently physically unfit for war service and the cause was said to be “melancholia attrib. to service;” in other words, depression, which was attributed to his military service. His degree of disablement was “30% then 20%.”

What he was doing during those years isn’t clear; his service record is illegible in places, but it is possible that the Regimental War Diary would be a source of information. His discharge certificate was issued by the Nottinghamshire County War Hospital.

Demob

War ended with the Armistice on the 11th November 1918, but the soldiers were not immediately demobbed. Although just about all the men wanted to go home at once, it was simply not possible. Not only would it have been practically impossible to process all men in a short period of time, the British army still had commitments to fulfil in Germany, North Russia and in the garrisons of the Empire. William was in England, but those who were abroad had to be brought home.

Regular soldiers who were still serving their normal period of service remained in the army until their years were done. Men who had volunteered or who were conscripted for war service generally followed the routine described below. Men with industrial skills, including miners, were released early. Those who had volunteered early in the war were given priority treatment, and the conscripts, particularly the 18 year olds of 1918, were left till last. Most of the war service men were back in civilian life by the end of 1919.

Before a soldier left his unit he was medically examined and given various forms including one which allowed him to make a claim for any form of disability arising from his military service. Soldiers who were still abroad spent some time in a transit camp near the coast before being able to sail home. On arrival in England, they would be sent to a Dispersal Centre, which was a hutted or tented camp or barracks. Each man was issued with a Protection Certificate which enabled him to receive medical attention if necessary during his final leave (William’s has survived and is shown below). He also received a railway warrant or ticket to his home station.

William’s Certificate of Identity and Provisional Protection Certificate.

The Certificate will act as a Protection Certificate for the soldier pending the receipt of his Discharge Certificate …

The discharge under para. 392 XVI King’s Regulations of the undermentioned soldier has this day been approved.

No. 351761

Pte. William Bateman Redwood

27th Durham L.I.

Address: 11 Dinnington Road, Woodseats Road, Sheffield

Signed by the officer in charge of Notts County War Hospital.

Stamped 19 May 1919

Original document provided by Dave Emsley

Home

William made his way back to his family in Sheffield, living at 11 Dinnington Road off Woodseats Road. He received a pension, which included an allowance for his two children. Eleven months after he was discharged from the army, William Redwood died at the Wharncliffe War Hospital at Middlewood, on the 14th May 1920.

A certificate issued by the hospital said that he died at 4.40pm of nephritis and uraemia, which were attributed to his Active Service. The reason for stating that death was attributed to Active Service was important and relates to the right to be awarded a military pension. It has also come to be one of the criteria for commemoration by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Nephritis is an inflammation of the kidneys, caused by toxins, infection or autoimmune conditions. Along with other trench diseases such as trench foot and trench fever, trench nephritis contributed to 25% of the British Expeditionary Force’s triage bed occupancy and was the major kidney problem of the First World War. The condition led to hundreds of deaths and 35,000 British casualties – it was possibly spread by rats. Basically, William’s death was caused by kidney failure. There is no concrete evidence that being gassed would be a cause of nephritis.

Below: William's death as notified by the Wharncliffe War Hospital

351761 Ex. Pte. Redwood Wm. B. (Late) 27th D.L.I.

This is to certify that the above named pensioner died in this Hospital at 4.50pm on the 14th inst. Cause of death:- (1) Nephritis (2) Uraemia. Due to Active Service. Signed Robert Gordon M.D.

Original document provided by Dave Emsley

Pension

So, was widow Emily’s claim for the pension denied?

It turns out that she was in fact granted the Widow’s Pension, which was state-funded and with an allowance for children under 16 years of age. She was turned down when she applied for what was called an “alternative” pension.

An ex-serviceman was entitled to what was called an “ordinary pension,” but there was also an “alternative” or salary pension, based on his pre-war income. If a disabled ex-serviceman thought that his army pension (plus any earnings he might make if he could work) was less than what he was earning before the War, he could be granted a higher rate of pension, not exceeding his pre-War earnings. It seemed a very complicated matter. There was a lot of resentment among ex-servicemen about pensions, and in 1919 a Select Committee on War Pensions recommended wide ranging improvements to war pensions provision, including a substantial increase to the alternative pension, which helped to diffuse much of the tension.

This “alternative pension” could be claimed by widows (forms are stamped with the letters APW). A pensioned widow could apply for this if she could prove that her husband had been earning more than the flat rate of pension for total disablement before he enlisted. If granted, this would be in lieu of the ordinary pension.

Not all women were granted a pension. A woman who married an ex-soldier after he had been discharged from the army would not get a pension if he later died from war wounds. Some women had their pensions withdrawn by the Local Pensions Office if they were judged to be behaving in the “wrong way,” for instance if they were accused of drunkenness, neglecting their children, living out of wedlock with another man or if they had an illegitimate child. Thousands of women wrote to the authorities to appeal for a pension. There was fear that if the pension was too generous, then it would mean that women would be discouraged from supporting themselves. “Eighteen shillings a week and no husband were heaven to women who, once industrious and poor were now wealthy and idle,” one man wrote to the Daily Express, complaining of the pension.[1]

I believe that it was this alternative pension which was denied to Emily, not her ordinary widow’s pension. An APW form (available via the Western Front Association and also via Ancestry on its Fold3 subscription) shows that Emily had applied for this alternative pension but was declined. The reason for ineligibility was given as “late husband’s PWES [Pre-war earnings] insufficient to qualify widow.” The date of the decision was the 4th May 1921, a year after his death. [both these sites are behind a paywall and there will be more records available. This card was kindly sent to me by someone with a subscription].

Emily was certainly not the only widow to have her application declined. Applying for an alternative pension was a complex procedure and it was up to the widow herself to provide evidence to support her application. Obtaining evidence of a husband’s pre-enlistment wage was very difficult. Record keeping at many businesses was not particularly detailed in the days before universal taxation, and firms had sometimes closed down by the time the widow would come to make her application. Those paid on piecework were also at a considerable disadvantage when it came to being able to prove their earnings.[2]

Nowhere near as many widows as were eligible were successful in their applications for alternative pensions. In 1919 there were 200,000 war widows, of whom only 18,000 had demonstrated that they were eligible for alternative pensions, just 9 per cent of the total. It was not in the government’s interests for widows to apply; had all those who were eligible done so, it would have cost the state an extra £18 million per year. New applications for alternative pensions were no longer allowed after 31 March 1921, although those allowed before that time continued to be paid.

Pre War Earnings were only relevant for the alternative pension application. A widow could only claim for an alternative pension if she was entitled to the ordinary widow’s pension. Therefore, it looks as if Emily did not qualify for the alternative pension because the calculation from her husband’s pre-war earnings would pay less than her ordinary widow’s pension.

[1] https://www.mylearning.org/stories/how-the-first-world-war-affected-families/797#:~:text=Pensions%20for%20war%2Dwidows,for%20any%20children%20under%2016.

[2] Para 2, Chapter 53 of the War Pensions (Administrative Provisions) Act 1919: Information from employers which now extends existing powers relating to the pre-war earnings of disabled servicemen to deceased serviceman: “The power of the Minister of Pensions under section fourteen of the War Pensions (Administrative Provisions) Act, 1918, to require information from employers and others for the purpose of ascertaining the pre-war earnings of a disabled person, shall be extended so as to include power to require information for the purpose of ascertaining the earning capacity of any such person and for ascertaining the pre-war earnings of a deceased person, and it shall be the duty of employers, and of any other person having knowledge thereof, to furnish any such information, and that section shall have effect accordingly.”

Above: this page from William’s Service Record shows, his widow Emily was eligible for the pension “under the usual conditions.”

Above: an APW form (available via the Western Front Association and also via Ancestry on its Fold3 subscription) shows that Emily had applied for this alternative pension but was declined. The reason for ineligibility was given as “late husband’s PWES [Pre-war earnings] insufficient to qualify widow.” Date: 4.5.1921.

Medals

William was awarded the British War Medal and the Victory Medal and the 1914/15 Star.

The 1914/15 Star was approved in 1918 for issue to officers and men of British Imperial Forces who saw service in any theatre of war between 5th August 1914 & 31st December, 1915 (excepting those who were eligible for the 1914 Star). William was in France for nine months, from the 13th April 1915 until the 14th January 1916. Recipients of this medal also received the British War Medal and the Victory Medal, and all three were sometimes irreverently referred to as Pip, Squeak and Wilfred.

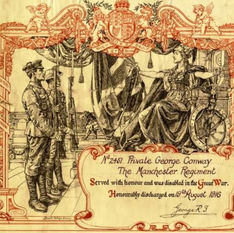

In addition, William was awarded the Silver War Badge and a certificate. This badge, which was approved in 1916, was also known as the Services Rendered Badge, Discharge Badge or Wound Badge, and it was issued to men who had been honourably discharged due to wounds, disability or sickness. Men wore it during the War to prove they had done their duty, and were not to be treated with contempt or even violence from those who thought they were shirking their duties. It was approved for issue to men who had served at home or abroad since the 4th August 1914. The scope was later widened to include eligible civilians, members of the Voluntary Aid Detachment and nurses.

William was buried at Abbey Lane Cemetery in Sheffield, as were many other ex-soldiers. This photograph of his headstone appears on the Wharncliffe War Hospital Website. “Gone from our home but not from our hearts.”

Note: his date of death is inscribed as 20th May 1920 and not the 14th as appears on the notice of death issued by the hospital.

SOURCES:

Findmypast and Ancestry for William’s War Record

Ancestry, Findmypast and the National Archives for the Medal Cards

The Wharncliffe War Hospital website for details about William’s grave etc. http://www.wharncliffewarhospital.co.uk/

eBay for the medal photographs

The Western Front Association for the Alternative Pension application form, also available through Ancestry’s Fold3 subscription

Photos and documents from Dave Emsley, William’s great grandson

Commonwealth War Graves Commission https://www.cwgc.org/

https://www.westernfrontassociation.com/